Check out more about Salam Tims and his work

Salam Tims — Writer & Digital Media Producer (Website)

Thoughts, memories, reflections, reviews and celebrations of fantastic tales . . .

Check out more about Salam Tims and his work

Salam Tims — Writer & Digital Media Producer (Website)

This blog is an exploratory celebration of the myths, dreams, and memories inspired by fantastic tales I’ve read or seen on screens over the long and growing span of my years.

What do I mean by fantastic? The dictionary says it describes the imaginative and fanciful, the extraordinary, bizarre, or exotic. That’s what I’m talking about here.

All my life, fantastic tales have been my refuge and delight, shaping my imagination and leaving me always wanting more.

My earliest memory of reading, at about five-years old, is following along as my older brother read a comic book to me. I still remember the cover and the title—ATOMIC MOUSE. It was indeed a fantastic tale of a super-hero —who happened to be a rodent—and I was hooked.

Around the same time, my brother took me to the neighborhood movie theater to see the first movie I can remember—WAR OF THE WORLDS. It fascinated and scared me witless—I watched much of it peeking from the rear of the auditorium–and I loved it.

My sense of the fantastic span the interval twixt ATOMIC MOUSE and TENET.

Growing up in the 1950s, I hated school and lived for books from the library, weekend movie matinees, and the occasional fantastic fare available on B&W TV. I quickly exhausted the science fiction shelves in the kid’s section of the library. I would hit the library on the way home from school, and spend the evening reading instead of doing homework; a pattern that persisted through high school and nearly flunked me out of college. Having exhausted the kid’s shelves, I conducted a running battle of wits with the librarians, trying to surreptitiously slip an “adult” title into the stack of books I was borrowing. Sometimes it worked, sometimes not.

I didn’t read much fantasy as a kid, only the Oz books—but all of them—and most of them in high school, when I had the reverse of my childhood experience of wanting to borrow “adult” science fiction. As a teen, I found myself mildly embarrassed wandering back into the children’s lit section to check out oversized illustrated Oz books—but I did love them.

During those juvenile years, I continued to entertain and often terrify myself at the movies. Any Saturday or Sunday afternoon when I could scrounge up the admission—often using money intended for my accordion lesson—I attended a double-feature matinee, usually sci-fi, mostly “creature features”, like CREATURE FROM THE BLACK LAGOON, and of course GODZILLA. These being the paranoid red-scare 1950s, there were alien-invasion films galore—like INVADERS FROM MARS and THIS ISLAND EARTH. Most of these matinee shows were “B” movies, made on shoestring budgets on black and white film with “hey kid, you could do this at home quality” flying saucers and aliens. I fondly recall some fantastic-few standout classics that are still watched and discussed today—films like THE THING (FROM ANOTHER WORLD), THE DAY THE EARTH STOOD STILL, and INVASION OF THE BODY SNATCHERS. It’s no surprise that several of those classics have been remade over time, some more than once.

On television, I grew up warped and weird watching 50’s shows like TWILIGHT ZONE, ONE STEP BEYOND, and SCIENCE FICTION THEATRE on a B&W TV that broadcast only three stations just eighteen hours per day. There were some fantasy tales scattered among the episodes of these anthology shows, but mostly fantastic science fiction.

The 60s, my teens, was a golden age of fantastic culture. Even mere mentions of the books that shaped my adolescent imagination would be too numerous to list here without transforming a post into an online catalog. Some personally resonant standout writers shaped my imagination. Heinlein (you know what book) helped quicken my boomer cohort’s counter-cultural “awakening.” Herbert (DUNE et al) got me thinking about systems on every level and inspired a career in systems. Vonnegut (CAT’S CRADLE et al) helped cultivate my humors—all four. Le Guin (LATHE OF HEAVEN et al) started me thinking about human culture on every level); Tolkien (LOTR) got me interested in epic tales and linguistics. Finally, maybe surprisingly, I have to cite Shakespeare. I read HAMLET—my first play—as a ghost story; same with MACBETH. A MIDSUMMER NIGHT’S DREAM—my all time favorite play—inspired lifelong dreams of fantastic faerie. These fantastic authors and others will inspire future posts.

In high school, movies began to contend with novels for control of my attention. In the 60s some fantastic movies “grew up”—along with their audiences—and became “films” or “cinema.” I’d always enjoyed “monster movies” for the sheer horror and now auteur-filmmakers were making horrors like PSYCHO and THE INNOCENTS, and one was about to create a new and enduring kind of monster in NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD. The same thing happened in sci-fi with films like ALPHAVILLE, SECONDS, FAHRENHEIT 451. Then—the year I graduated from college—2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY set the bar at a new level for the next generation of sci-fi film.

On television, there was a lot of sci-fi and fantasy during my teens, much of it not so good—with a few standouts like the Ur-STAR TREK, THE PRISONER, and THE OUTER LIMITS.

In the half century since college, most of what I’ve read has been fantastic—speculative fiction—sci-fi and fantasy. My film watching history has been more diverse but fantastic tales dominate my list of all time favorites. I largely abandoned TV for decades, only to rediscover it in its new 21st-century golden age and now the amount of truly fantastic fare on the small screen is—fantastic.

In future posts, I’ll explore fantastic tales, past and present, from many angles, always with a view toward entertainment, information, and inspiration. I invite you to follow along and join me on this fantastic journey.

Check out more about Salam Tims and his work

What is a human being?

My rating: 4 of 5 stars

This is a wonderful novel, beautifully written, with an AI protagonist/narrator (Klara) who is the most “human” character in the story. What makes someone or something a human being? This novel suggests that it is the capacity for caring and love for another that makes us human and Klara embodies selfless loving care for her human companion Josie. Klara is capable of every human gesture and act and yet, in her descriptions of her own stream of consciousness, it is very clear that her perceptions and thought processes are more than, other than, human. The author makes us see how different Klara is, while also showing her caring loving nature. I usually “forget” novels as soon as I finish them. “Klara and the Sun” has stayed with me and I expect it will.

View all my reviews

Fantastic Literary Fiction or Sci-Fi?

Is “Dead Astronauts” (literary) fiction or science fiction? It has some of the genre tropes of sci-fi — a future post-apocalyptic dystopian setting and premise. Its unconventional — sometimes seemingly incoherent — narrative style make it far more literary than most novels in any genre, including sci-fi. Its publisher branded “Dead Astronauts” as science fiction—undoubtedly to make it more commercial. My local library catalogued it as Fiction. The library had catalogued VanderMeer’s “Souther Reach” trilogy (starting with “Annihilation”) as sci-fi and “Borne” as Fantasy. “Dead Astronauts” is (kind of) a nominal sequel to “Borne”. Go figure!

Like all VanderMeer’s work, this novel asks much of the reader. If James Joyce or Bertolt Brecht had written science fiction, it might be something like this. Story emerges — obliquely and almost incoherently —from phenomenal descriptions of characters in bizarre situations distributed across multiple timelines in alternate realities. It would take a second or third reading to enable any informed opinion on ultimate coherence or its lack. I honestly can’t offer a synopsis after a single reading.

Why read it? You may well ask! If you are seeking a conventional sci-fi story with relatable (or even clearly defined) characters pursuing coherent plot lines to a satisfying conclusion, this is probably one for you to skip. Personally, I like to be challenged. As a reader who writes, I find VanderMeer’s language cryptically enchanting— sometimes leaving me in the same state of befuddled awe and wonderment I felt on first listening to the Beatles’ “Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Heart Clubs Band”. He tosses off phrases so unconventionally beautiful that I stop in awe of the language. As a writer, I find his lack of convention truly liberating. All these qualities landed “Dead Astronauts” in the local library’s Fiction shelves and on my list of books worth reading at least twice.

Ironically, if I were not already following Jeff VanderMeer’s writing and if it were not for the novel’s sci-fi attributes, I probably would have passed on reading it. I’ve now read five of VanderMeer’s novels, beginning with “Annihilation, continuing with its sequels, then “Borne” and now “Dead Astronauts”. I’m a fan.

“Annihilation” was challenging, and each novel since has been progressively more so. Each novel has been grounded in a world further down the road to an end predicted by the first title—annihilation. In “Dead Astronauts” we are in a vision out of Yeats where things have already fallen apart; the center did not hold; Bethlehem is ruined along with everything else, and rough (genetically engineered and mutated) beasts roam the land. In that progression, the writing moves from dreamlike in “Annihilation,” nightmarish in its sequels, to surreal and disjointed in “Borne” and even more so in “Dead Astronauts”.

With each novel, at some point I asked, “Do you really want to finish reading this?” Each time, for the reasons cited above, the answer was, “Yes!” Each time I came away glad of it.

Call it literary fiction or sci-fi, “Dead Astronauts” (and Jeff Vandermeer’s writing) is a trip worth taking.

Like many fans of science fiction, I enjoy tales of time travel. I read HG Wells’ The Time Machine at an early age and have sought out entries in this venerable sci-fi sub-genre ever since. Over the course of my reading lifetime, concepts from theoretical physics have seeped out of quantum mechanics, cosmology, and particle physics into the popular culture and heavily influenced sci-fi in general and time-travel tales in particular, inspiring novels, screenplays, and TV series that are increasingly complex, sometimes to the point of cryptic inscrutability. Wormholes, temporal paradox, parallel timelines in parallel universes that branch off and or into our own here and now. It would be reasonable to say that sci-fi has been the main vehicle for bringing these esoteric concepts into mainstream culture.

A really good time travel story often requires more than one reading or viewing just to be understood and to figure out whether or not its time loops, parallel and intersecting timelines, and paradoxes ultimately add up to a coherent whole without “holes” in the story. It’s a challenge for the creator and maybe even greater challenge for the audience. Meanwhile, like any story, a time travel yarn must hook the audience with compelling characters, dramatic conflicts, interesting settings and situations. When it all works, it’s sublimely fantastic storytelling.

Dark, a German TV series that ran three seasons on Netflix, is tagged (on IMDb) as a “crime, drama, mystery” and it delivers on all three genres. It begins with children disappearing and the discovery of other children’s bodies, establishes a set of complex compelling characters in manifold (and confusing) relationships, and sets up a mystery of who took the children, where and whe, and why. Personally, I would tag its genre blend as “mystery, drama, sci-fi.” Like any entertaining mystery, clues abound and intrigue deepens.

The overarching ambience and emotional tone of the series is best described by its title—it’s dark, with lots of guilt over sins of the past that ripples across generations. Underlying everything is a very complex science-fiction premise that explores the paradoxes of time travel. As if its large cast wasn’t complex enough, we see many characters at two or three stages of their lives, played by other actors in scenes from past and present storylines. Sometimes they cross timelines. One of the missing children from the present travels back in time whence he grows up to father a teenage protagonist (who had been a contemportary) in the present timeline) is dismayed to discover that his girlfriend is his father’s niece, a genetic first cousin. You really can’t tell the players without a program and it’s not surprising to find a Wikipedia article on Dark that attempts to sort it all out, going so far as to lay out detailed family trees of the main characters, including some strange loops. It’s still something of a mystery to me and I’m enjoying it. It requires some effort and, in a way, adds an interactive element to the experience.

I watched this first season in 2017 and found it very absorbing and very confusing. When subsequent seasons were released, I decided to watch it a second time before starting the second season. That helped me sort things out and I still wouldn’t be able to write a coherent season synopsis that was more than a ridiculously complicated logline. In part, that’s a function of my viewing habits—I like to watch several series in parallel and don’t watch that often. As a result, it took me six months to watch every episode a second time. Some shows cry out for binge watching and I think Dark would make more sense more readily, if watched over a week or a couple of weekends.

I intend to watch the second and third season and have high hopes that coherent comprehension will emerge. If not, I may have to watch the full series again. Dark may not be easy viewing but it’s highly entertaining (despite its gloomy style) and well worth a second (or even third) viewing to grok its fullness.

Ray Bradbury was a prolific writer—of short stories, novels, plays, screenplays, essays, and poetry. As one title in this collection of essays asserts, “Doing is being,” you are what you do. What Bradbury did was write—at least 1000 words every morning throughout his life. As he describes it, this wasn’t work so much as play. He loved writing; it was his favorite thing to do and by his own definition of being, he was a writer first and last.

More celebrations of writing, and exhortations to write than instructions in the art, these essays do describe how Bradbury wrote and do offer some advice to would be writers. His writing process was essentially — discovery. He sat down at his typewriter—his frequent allusions to that wonderful word machine make me wish I still had one—to see what was on his mind in that moment, and started putting words on paper in a process of free association. Words led to other words and phrases and out of that stream of consciousness settings and characters emerged and the characters led him into their stories. He acted as medium or channel, not editing, not worrying about typos, spelling, or grammar, like a hound finding the scent of a story and pursuing wherever it led. Craft—editing, polishing, structuring—all happened over as many subsequent drafts as needed to finish the work. In his early career, he saw the editorial drafts as drudge work. In later years, as he mastered word and story crafts, he took more pleasure in that work.

What tips and advice does he offer, other write every day? Here, in no particular order, are the notions and ideas I took away from this first reading (I expect to reread it for inspiration any number of times):

Live in your body and pay attention. The myriad mundane details of life are a sea of sensory information. Attend to the people you see every day and the strangers you encounter. They are all characters in countless stories. Study your surroundings. They are all settings in which stories can and do play out. Observe. Render your observations as words.

Note fleeting ideas–words, phrases, and seeds of story. Keep a list and revisit it from time to time to see what might have sprouted over time.

Feed and heed your Muse. A child of the twentieth century, Bradbury locates and identifies that source of ideas and inspiration in his creative unconscious mind. Feed it generously with books, films, series, music, art, and experience. It’s all grist for your unconscious creativity and may surface in surprising combinations as free associations that drive your conscious creativity. I would add–be mindful what you ingest As we are what we eat, for good or ill, we are also, what we read, and watch, and hear. Let your input be appropriate to your desired output. When your Muse does whisper in your inner ear, pay heed. Honor your Muse by paying attention. Write those whispers, however fragmented, and make them your secret sacred sutras to be pondered for direction and inspiration.

Mine your personal story. Bradbury says that most of the characters in his many stories were drawn from the family, neighbors, and townspeople of his midwestern youth. They not only populated his idyllic “Greentown” novels (Dandelion Wine, Something Wicked This Way Comes, and Farewell Summer) but also the colonists and Martian ghosts of his Martian Chronicles. We are all stories that too often we feel are too dull and prosaic to be worthy of literature or escapist fiction. Bradbury’s writing shows how the glorious can be mined from the ordinary and the oft repeated advice to “write what you know” doesn’t preclude using what you know best—your own story—as the basis for literature, even fantasy and science fiction. Bradbury lived in Ireland for six months while writing the screenplay for John Houston’s MOBY DICK. He found scant enjoyment and inspiration, so he thought, in the experience. Over subsequent years, Irish characters and settings emerged in his associative writing process that flowered as short stories and plays.

When writing stops being fun, step away from it. Give it a rest. Don’t struggle. Leave it to your Muse and play at (maybe write) something else.

Write for pleasure and the simple joy of writing. Write what you want to read. Don’t try to be literary; simply write as well as you can. Don’t write for the market, for money or fame. Write for the joy of writing.

There’s more gold in these essays than I have recalled, and I may have contaminated some of Bradbury’s gold nuggets with my own rumination. I’ve ingested his words, fed them to the Muse and look forward to further amusement as they ferment and sprout in whispers that will drive my own play.

Erin Morgenstern crafts a story-labyrinth

What’s your story, the one you live by, the one you are living—the one you tell yourself to live? We are all stories and we live to consume stories from and about others. Sometimes, we write and read a story about story and story telling. It’s a venerable genre and a difficult one to try, as writer or reader, requiring a sensitive touch lest it cease to be fiction and veer toward something drier, airier, pedantic. “The Starless Sea” is a story about story and story telling—a very ambitious and very complex story with other stories nested within it on multiple levels, almost like a video game.

Video games are another form of story telling. Games outsell books (and movies) worldwide. More people play stories than read them.

Erin Morgenstern has said that she immersed herself in video games while writing her books, especially this one, and it shows heavily, some say too heavily, in the book’s complex structure, which intertwines several non-linear plot lines through which characters wander in loops—lost in time and place, confused, and frustrated (as are some readers).

All storytelling is (or can be) immersive. Narrative stories tend to be linear, sometime multi-linear. By words (or images) alone, they immerse the audience (reader) in an interior imaginative experience. The narrative storyteller controls the story line, leading the audience (reader) through the story along a singular path to a single end. Greater complexity places greater demands on the memory and imagination of the audience.

A game is a story structured for active participation by the audience (player) who enters into the story and directs branching story lines by taking actions and making decisions. Games immerse the reader in an exterior spectacle and sound. Digital art informs the player’s experience of story in a game. In a game structure, the storyteller sets the stage and characters, and plots multiple paths (story lines) for the audience (player) to follow to one or more endings. Each player directs and affects the storyline, climax, and resolution by choosing alternatives. Games are non-linear by design. Games, especially computer-based video and VR games can be complex because the game manages the complexity for the player.

In “The Starless Sea”, Ms. Morgenstern attempts to render the exterior complexity of a video game within the interior imaginative experience of the reader. In lieu of digital sights and sounds, she deploys dazzling descriptions, creating images and situations that can induce the waking dream state sought in all storytelling. The game space includes our “real” world but plays out mostly in an immense, seemingly infinite “underground” world devoted to stories and books rendered in myriad scribed media, housed in libraries of every kind, all surrounded by a mysterious starless sea. Time and space are mutable. The burden of managing that complexity falls heavily on the reader. For some readers, including me, that is a delight. Others may think she would have served this story better by designing and building it as an actual game.

“The Starless Sea” IS a game wherein the player (the reader) must solve the mystery of what’s going on in all these stories. What’s the back-story? Who are these characters and how do their stories relate? What is the meaning of the symbols–crown, key, sword, and bee—that figure so prominently? What about the cats and owls? Who or what is the Owl King? Some of those answers are provided and some not so clearly. You may need to read the book more than once to figure it out and I suspect, like a game, it has as many explanations as readers.

Most ambitiously, the story addresses the capital-M Mystery of story itself. What is it? How does it shape its audience? How does it shape the “real” world? The book is layered with nested manifold metaphors and similes that amuse, bemuse, beguile, and maybe irritate the reader at every turn of phrase, page, and plot.

Stories come to life in the telling—quicken within us or do not. We are drawn to follow the tale—spell bound, enchanted, entertained—or not. “The Starless Sea” did cast a spell upon me, did enchant and entertain and I was reluctant to see it go. I can no more provide a precise recap of its story and stories than I can for a dream. I expect / want to dream it again.

A classic tale for every age

Are you one who finds or has ever found carnivals and side shows both fascinating and creepy? Are you perhaps one of the “October” people, drawn to the fading colors and dying light of shorter cooler days? Have you tasted the tart sweetness that lies at the heart of bitter melancholy?

Ray Bradbury certainly did and poured all that and more into his classic fantasy novel, Something Wicked This Way Comes. Like most of his novels, this tale had its genesis in his Midwestern youth. This is one of his “Greentown” books, set in the mythologized and renamed Waukegan Illinois of his boyhood—properly paired with his Dandelion Wine, a dark autumnal shadow to that novel’s bright sunshine. It’s not a sequel but the books are thematically tied—and that’s a fitting topic for another post.

Its themes include time’s passage, youth craving maturity and freedom, maturity looking back upon youth with regret, the strained bonds of both friendship and parent-child love, and the sinful siren songs of dangerous shortcuts twixt youth and maturity and damaging abdications of maturity’s responsibilities.

Jim Nightshade, chafes under the anxious smothering care of his widowed mother and wants to grow into greater freedom as fast as he can. Will Holloway, his best friend, is in no rush, mindful of how his father’s age exceeds his mothers. That father, like many inhabitants of Greentown, rues his age, feel’s death’s immanence, and longs for paths untaken, chances not taken, energy unavailable for greater engagement with his son.

Into this mix of desire and regret, steams the ancient steam train hauling Cooger & Dark’s Pandemonium Shadow Show, something more than a carnival with mysterious sideshows, something wicked. Its steam calliope plays a siren song of dreams fulfilled and youth regained. The denizens of Green Town respond to its call, some more than others. Some dreams become nightmares.

It is indeed a pandemonium. Its sideshows display panoply of unnatural human disfigurements. Its maze of mirrored infinities can trap susceptible souls. On its carousel, time spins forward for some and backwards for others to the dismay of both. Sinister Mr. Dark presides over the shadow show and sets his eye upon restless Jim Nightshade as a fitting partner in pandemonium. Will Holloway needs his father’s help to save Jim from his own dangerous yearnings and Dark’s depredation.

I have read this novel several times at different stages of my own passage through time. As a youth, I identified strongly with Jim Nightshade’s desire from adulthood and liberation from the strictures of youth. I too wanted the carousel of time to spin me more rapidly into more exciting and dangerous adventures and indeed, it did, spinning me wildly and sometimes prematurely both to grownup delights and to mature dismay at my youthful foolhardiness. In my late maturity, I identify more with Mr. Holloway, ruing the inexorable fade of youth’s vigor and regretting some things done and even more things not done that might have been. A classic work offers itself anew to every age, within your own life and across time to different generations. Ray Bradbury wrote more than one classic and Something Wicked This Way Comes counts as one such, at least to this reader.

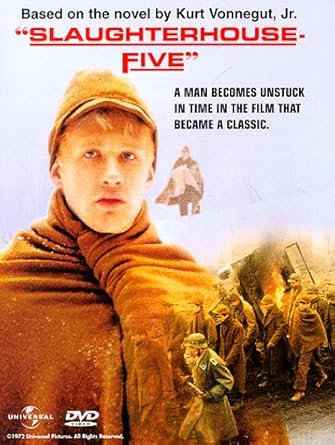

Billy Pilgrim is “unstuck in time“— Aren’t we all?

Director (THE STING, BUTCH CASSIDY AND THE SUNDANCE KID) George Roy Hill’s film adaptation Kurt Vonnegut’s 1969 novel Slaughterhouse-Five, or The Children’s Crusade: A Duty-Dance with Death is, in my opinion, that rare thing—an adaptation that’s maybe better than the original. That’s not to say that the novel is not a great book; it’s one of the great anti-war novels, worth ranking alongside Catch-22, All Quiet on the Western Front, Johnny Got His Gun, and The Red Badge of Courage, to name a few such. (Unlike most of these, it’s also hilarious.) I say, “Maybe better” because I only read the novel once, after having first fallen in love with the film, which I have screened many times. For years, I considered it my “favorite movie” and it remains a personal contender. So, I may be biased.

It’s one of those nearly “perfect” movies wherein all the pieces fit together into a seamless integral whole that is greater than its parts, wherein every scene, every action, every speech reveals character, advances the story, sets up something that follows or pays off on a prior set-up. Stephen Geller’s screenplay is a model of craft that every aspiring screenwriter would do well to study. An emotionally perfect film score augments the screenplay with performances of Bach by Glen Gould, along with Pablo Casals and the Marlboro Festival Orchestra. The sequence that introduces Billy, his fellow POWs, and the audience to the “fairy tale” city of Dresden, is a masterpiece of music and picture editing that sets up the ultimate destruction of city and citizenry ad profound tragedy.

It’s the story of Billy Pilgrim, an innocent soul, who becomes “unstuck in time” after surviving an otherwise fatal plane crash and near-death during subsequent brain surgery. Forever after, he is doomed—or blessed—with frequent and involuntary jumps between past—and future—events in his life. Much of the story is anchored in his experiences as a German POW who survives the horrific American firebombing of Dresden, as had Kurt Vonnegut. Those sequences earn novel and film their “anti-war” credentials. His “time travel” and adventure as an alien-abductee to the planet Tralfamadore qualify it as science fiction.

The film’s structure follows Billy’s jumps back and forth in time. Multiple non-linear story lines trace his life before, during and after his WWII misadventures. The jump cuts between story lines are always and ingeniously “triggered” by some story device–a situation, a line of dialog or sound effect (on or off-screen) or a visual image that associates two scenes in different story lines. The editing, by legendary Dede Allen, is flawless in its timing and precision. This structuring perfectly mimics the way associative memory works and offers a clue, or suggestion, that allows us to interpret the entire story as a figment of Billy’s multiply traumatized (by war and then by a fall from the sky into near-death) mind. In other words, is he unstuck in time or just lost in memory and imagination? The answer to that question either qualifies or disqualifies the science fiction genre designation for both book and movie. Personally, I don’t feel the need to select one interpretation or the other, feeling that holding both in mind simultaneously is itself a way of suspending time and transcending worlds.

The story is peopled by wonderful and sympathetic characters, some of them in cameo appearances from other novels in Vonnegut’s opus, like Howard Campbell, Junior (from Mother Night), Eliot Rosewater (from God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater, or Pearls Before Swine), and Bertram Copeland Rumfoord from The Sirens of Titan). Even Billy’s lifelong nemesis and ultimate assassin, Paul Lazzaro is made sympathetic by small touches that illustrate his inner torment. The German citizens of Dresden offer a gallery of humanity that is made heartbreaking by their collective doom as victims of war. We watch vignettes of everyday life, already knowing these beautiful people are doomed to a horrible fate.

Somehow, like the novel, the film manages to intermingle all this tragedy with comedy. That’s the genius of Vonnegut. He enables us to feel simultaneously traumatized while alternately laughing without either emotion undercutting the other. He mixes images and situations of horrifying reality and hilarious fantasy in ways that enrich our appreciation of both.

Whether we choose to believe that Billy travels in time and journeys to an alien planet or believe that both are his psychic defense mechanisms against life’s tragedy, our experience of his experience is entertaining, moving, and joyful.

Like Billy, we are all “unstuck in time”, consciously and unconsciously jumping continuously between past memory, present experience, and future fears, hopes and dreams. Like him, we can’t help it. We come “unstuck” from “here and now” to “there and then”, more often than not.

Like Billy, we might all do well to take to heart the Tralfamadorian teaching that,

“A pleasant way to spend eternity is to ignore the bad times and concentrate on the good.”

Kim Stanley Robinson’s sci-fi prophecy and prescription for human survival

Kim Stanley Robinson (KSR to sci-fi readers) is a master novelist with a penchant for realistic (no space opera, faster-than-light starships, or galactic empire) science fiction dealing with humanity’s prospects over the next few centuries. Much of his work deals with space exploration and settlement. His Mars trilogy—RED MARS, GREEN MARS, and BLUE MARS—is an epic imagination of how humans might claim, fight over, and “humanize” a new world. I loved the Mars books and consider his novel 2312 to be one of the best depictions of human colonization of the solar system I’ve read. His writing can be categorized as “hard” sci-fi in that it is all grounded in realistic projections of current science and technology. Beyond STEM disciplines, his work also draws upon extensive research in social and life sciences. He is a polymath and a humanist.

He has turned his attention to climate change on Earth in two novels: NEW YORK 2140 and most recently THE MINISTRY FOR THE FUTURE (TMFTF). Some critics have found fault with the former work as too optimistic. I doubt that many will say the same about his latest.

TMTF is grimly realistic, even horrifying, in its depictions of climate change and its probable impact on humans and human institutions over the middle decades of this century, which he rightly describes as an evolutionary “bottleneck” and possible extinction event for most life on Earth, including humans. It reads like a collaboration between the late sci-fi master, John Brunner (STAND ON ZANZIBAR, THE SHEEP LOOK UP) and climate activist Bill McKibben (DEEP ECONOMY: The Wealth of Communities and the Durable Future, EAARTH: Making a Life on a Tough New Planet, THE END OF NATURE). I have no doubt KSR has read both authors, as have I. The structure and style of the novel—multiple character points-of-view, interwoven storylines, and vignettes—is very much like Brunner’s work. Like McKibben’s books, it is peppered (maybe “seeded” is a better term) with densely factual non-fiction segments about numerous subjects, including the probable near-term consequences of climate change —physical, political, social, and economic—and what can aptly be called “tutorials” on geology, meteorology, monetary theory, capitalism. A recurring theme is that socio-economic inequality lies at the root of climate change and drives our resistance to do anything about it. You will not come away from this book rooting for the 1-10% of humanity that owns 80-90% of the world’s wealth and virtually runs its governments. You may also come away ashamed and embarrassed at how the political economy of the U$A is the worst offender driving climate change and likely the last adapter of any moves to halt and reverse it.

Don’t let any of this put you off! The book is ultimately albeit cautiously optimistic. It describes the many ways that science and technology can be harnessed to slow the movement of the world’s glaciers into the seas, and to reduce and even draw down the build-up of carbon that is cooking our oceans and atmosphere. It describes how the power of the world’s national banks might be harnessed to issue “carbon coins” that encourage and empower those technologies. It describes how the world’s suffering masses, not its ruling class, ultimately rise up in myriad movements to force change.

It’s also a page-turner—though you may be tempted, as I was, to skim some of the denser exposition of economic theory. I “whipped through” its 563 pages in less than two-weeks of bedtime reading. I strongly recommend reading it and hope it will find its way into a TV miniseries, though I’m not holding my breath on that. Check it out!

Artful Genre or Hollywood Hype?

According to many—maybe most—film critics and writers, there’s no such thing as “elevated horror”, an expression they dismiss as pretentious posturing or marketing hype. Tell that to Hollywood. As a serious—albeit (as yet) unproduced—screenwriter, currently marketing a horror script, I am often confronted by producer requests for “elevated horror.”

What is elevated horror? According to one writer, the phrase “refers to movies that don’t rely heavily on jump-scares or gore, but are so emotionally and psychologically disturbing that they traumatize even the most seasoned of horror buffs. Many of the films also seem to contain allegorical meanings.”

Is that another way of saying they are artful? Certainly, horror films can be artful. I’ve written recently about a couple of examples—Frankenstein (1931) and Alien (1979). In recent years, the works of three directors have frequently been cited for “elevated horror”: Ari Aster, Jordan Peele, and Robert Eggers. This is the first of three articles, one for each of these artists.

Ari Aster grabbed the brass ring with his debut feature, HEREDITARY, in 2018 and raised critical and audience eyebrows the following year with his second, MIDSOMMAR. Both films are tagged (in IMDb) as “Drama, Horror, Mystery.”

I’m writing about MIDSOMMAR because it satisfies all my criteria for a “fantastic tale”: It’s imaginative and original in concept. The only comparable work I can think of is the original British film, THE WICKER MAN (1973), and this one goes far beyond that in its exploration of folkloric ritual horror. It’s outstanding in its screenplay and execution. In my rating system it’s a “5”—worthy of repeated viewings, analysis, and study. It’s truly bizarre — discontinuous with everyday reality—unlike anything I’ve ever seen—and exotic in its exploration and presentation of culturally remote Swedish folklore.

As drama, it tells the story of Dani (aptly named for an ancient goddess) who journeys from orphaned survivor of unthinkable family tragedy, through a frustratingly unsatisfying relationship with a deceitful and self-absorbed man to an unimagined destiny in a remote Swedish midsummer ritual. She is sympathetic, generous and intelligent, unlike her boyfriend and his peers, who all pursue this adventure for various selfish reasons. Desperately hungry for love and family, Dani just wants to be with the ironically named Christian, the man she loves who does not really love her. She longs for her lost family and sister and ultimately finds both family and sisterhood, albeit under bizarre circumstance.

As horror, the story is a slow build—with only one instance of real horror in its first half—to a literal conflagration of relentless fright, shock, and revulsion in the third act, which is almost unbearably horrifying. There are no monsters, no shock-scares by things leaping out from shadows. The horror slowly gathers and builds mounting suspense, until it overflows and overwhelms in an avalanche of visceral emotion. The antagonists who deliver the horror are wholesome country folk, true to their ancient traditions and suffering palpable empathic pain along with their victims.

The central mystery is hinted at with myriad clues and forebodings throughout the second act. As finally unveiled in the final scenes, we realize that it’s capital “M” Mystery—ancient and deadly. Anyone with any knowledge of European folklore or its pagan history will suspect where the clues are pointing and still likely be emotionally unprepared for the ultimate reveals.

Speaking of mystery and clues, this is a near perfect screenplay in the sense that every action, virtually every line of dialogue, every composition, in addition to advancing the story, sets up and foreshadows things to come. Three fourths of the story is set up and the pay-offs in its final act exceed our worst fears and anticipation.

So, returning to the initial question: is this “elevated” horror. I would say, “Yes,” and I offer my own definition:

Elevated horror delivers the visceral impact of the genre in artful forms, untrammeled by the genre’s familiar and formulaic tropes and convention.

By that standard, Ari Aster has written and directed an elevated horror masterpiece that establishes him as a master filmmaker. Considering that MIDSOMMAR is only his second feature, one looks forward to his future work with anticipation.

Ray Bradbury and Halloween—yay!

This year I wanted two things for Halloween—an appropriate Halloween read and at least a brief respite from horror, both in fiction (which I enjoy) and in life (and there seems no end to real-life horror these days). Ray Bradbury’s THE HALLOWEEN TREE, which came to my attention just at the right time, satisfied both wishes. As the title says, it’s all about Halloween and it’s a welcome alternative to horror—real and imagined. BUT—you may interject—it’s a book for kids! So? Halloween brings out the kid in me—as I grew up, it was always my favorite holiday AND I like well-written children’s books—AND this is RAY BRADBURY, one of my lifelong mentors in wordcraft and spellbinding storytelling. This neat little novel did not disappoint. It sends a group of twelve-year-old boys on a journey through time wherein they learn Halloween’s “hidden” history and each makes a profound sacrifice to save the life of a friend. It ranges from cave dwellers huddled around a fire, to Egyptian tombs and mummies, to British druids, to the Notre Dame Cathedral, to Mexico for the dia de los Muertos. Like most of Bradbury’s work, it’s limited to a kind of literary equivalent to Norman Rockwell’s nostalgia for a never-quite-real Americana and still, for all that, it’s a beautiful cascade of words and phrases by a master writer and storyteller with an expansive and generous spirit. It lifted my own spirits in this darkening season and that’s just what I wanted.